ToadKing

Illegal Lawyer

Representative

Public Defender

Supporter

Aventura Resident

Change Maker

Popular in the Polls

Statesman

Order of Redmont

ToadKing__

Representative

- Joined

- Apr 4, 2025

- Messages

- 416

- Thread Author

- #1

Username: ToadKing__

I am representing a client

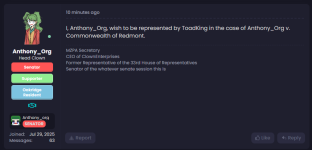

Who is your Client?: Anthony_Org

File(s) attached

What Case are you Appealing?: [2025] FCR 117

Link to the Original Case: Lawsuit: Dismissed - Anthony_Org v. Commonwealth of Redmont [2025] FCR 117

Basis for Appeal:

- Any member of the public can challenge constitutionality without showing personal harm; but

- A member of Congress lacks standing to challenge an Executive Order that restricts a statutory body serving Congress

If ordinary citizens have standing to challenge constitutionality, then surely a member of Congress - whose institutional ability to legislate is directly affected by the challenged Executive Order - has at least equal standing. The Court's dismissal creates an absurd hierarchy where ordinary citizens have broader standing than legislators to challenge restrictions on legislative functions.

The Plaintiff brings this challenge both as a citizen exercising the public check described in [2025] FCR 87 and as a Senator, whose institutional responsibilities are directly affected by Executive Order 37/25's restriction on the Legislative Service Commission.

The Constitution does not require such procedural gymnastics before courts can address constitutional violations. Individual members of Congress, like all citizens under [2025] FCR 87, have standing to challenge whether executive actions comply with constitutional requirements.

Section 18(1)(a) of the Constitution grants the Federal Court original jurisdiction over "Questions of constitutionality."

This case presents a pure constitutional question: Does Executive Order 37/25 exceed the President's expressly granted powers under Section 42 of the Constitution?

Section 42 is unambiguous:

Section 20(1)(b) grants the Supreme Court jurisdiction over "Resolving disputes between government institutions," but this jurisdiction is concurrent, not exclusive. Nothing in the Constitution strips the Federal Court of jurisdiction over constitutional questions merely because two branches are involved. If the drafters intended for all inter-branch disputes to go directly to the Supreme Court, Section 18(1)(a)'s grant of jurisdiction over constitutional questions would be meaningless in any case involving government parties.

The Federal Court has jurisdiction, declined to exercise it, and thereby committed reversible error.

Whether the President exceeded constitutional authority under Section 42 is precisely the type of question courts exist to decide. Judicial review of executive actions for constitutional compliance is not a political question - it is the essence of the judicial power vested in the courts by Section 13 of the Constitution.

The Court's reasoning would immunise all executive actions from judicial review whenever Congress has theoretical alternative remedies. This cannot be correct. The Constitution establishes three coequal branches precisely so that each can check the others. The judiciary's check on executive overreach is judicial review, not abdication.

This is the second time this judicial officer has incorrectly invoked the political question doctrine to avoid deciding a justiciable legal question. In ToadKing v. Commonwealth of Redmont [2025] FCR 106, the Court dismissed a challenge to Executive Orders that violated the State Commendations Act's timing requirements, holding:

The pattern is clear: this judicial officer has systematically expanded the political question doctrine beyond recognition, using it to avoid deciding cases that clearly fall within the court's jurisdiction. This approach undermines the separation of powers by immunising executive actions from judicial review.

If individual members of Congress lack standing, ordinary citizens lack standing under the Court's reasoning (contradicting [2025] FCR 87), and "Congress as an institution" must pursue alternative remedies, then no judicial review is available. This immunises executive actions from judicial scrutiny and upends the constitutional system of checks and balances.

1. Contradicting its own precedent in [2025] FCR 87 regarding standing to challenge constitutionality

2. Declining jurisdiction over a constitutional question within its express jurisdiction under Section 18(1)(a) of the Constitution

3. Misapplying the political question doctrine to avoid deciding a justiciable constitutional question

4. Creating an impossible requirement that "Congress as an institution" must sue, contradicting [2025] FCR 87's recognition that individual citizens can challenge constitutionality

This case presents a straightforward legal question: Does Executive Order 37/25 comply with the Constitution's Section 42 requirement that Executive Orders "must only be used as a mechanism by which the President can exert powers expressly granted to the Executive within the Constitution"?

The Federal Court has jurisdiction to answer this question and should have done so. The dismissal should be reversed and the case remanded for decision on the merits.

Supporting Evidence: https://www.democracycraft.net/thre...alth-of-redmont-2025-fcr-87.31073/post-117121

PREAMBLE

We the people, of the Commonwealth of Redmont, in order to form a more perfect country, establish this Constitution to guarantee the preservation and protection of Justice, promote the general welfare of our citizens, and secure the liberty of our participation in the governance of this country. All citizens and the Government of the Commonwealth of Redmont will abide by these here set principles to unite as an indissoluble nation, the Commonwealth of Redmont.

This Constitution is the highest law of the Commonwealth. It binds all...

I am representing a client

Who is your Client?: Anthony_Org

File(s) attached

What Case are you Appealing?: [2025] FCR 117

Link to the Original Case: Lawsuit: Dismissed - Anthony_Org v. Commonwealth of Redmont [2025] FCR 117

Basis for Appeal:

I. THE DISMISSAL DIRECTLY CONTRADICTS THE COURT'S OWN PRECEDENT ON STANDING

The Federal Court dismissed this case for lack of standing, holding that "no harm was done to [the Plaintiff] personally" and that any harm "would be to the Congress as an institution, not to the individual members." This holding directly contradicts the same judge's decision in malka v. Commonwealth of Redmont [2025] FCR 87, where the Court cited another ruling in Ko531 v. Commonwealth of Redmont [2024] FCR 33:This holding establishes that citizens need not demonstrate personal damages to challenge the constitutionality of government actions. Individual citizens - including members of Congress - have standing to challenge whether executive actions comply with constitutional requirements. The Federal Court cannot simultaneously hold that:Members of the public can challenge the constitutionality of laws within the Federal Court. While they may not have specific damages related to the application of the law, they can challenge whether a law follows the parameters for being a law. In practice, it is considered a Check the public has on the government to ensure only legally acceptable laws are passed.

- Any member of the public can challenge constitutionality without showing personal harm; but

- A member of Congress lacks standing to challenge an Executive Order that restricts a statutory body serving Congress

If ordinary citizens have standing to challenge constitutionality, then surely a member of Congress - whose institutional ability to legislate is directly affected by the challenged Executive Order - has at least equal standing. The Court's dismissal creates an absurd hierarchy where ordinary citizens have broader standing than legislators to challenge restrictions on legislative functions.

The Plaintiff brings this challenge both as a citizen exercising the public check described in [2025] FCR 87 and as a Senator, whose institutional responsibilities are directly affected by Executive Order 37/25's restriction on the Legislative Service Commission.

The Constitution does not require such procedural gymnastics before courts can address constitutional violations. Individual members of Congress, like all citizens under [2025] FCR 87, have standing to challenge whether executive actions comply with constitutional requirements.

II. THE FEDERAL COURT HAS EXPRESS CONSTITUTIONAL JURISDICTION

The Court dismissed for lack of jurisdiction, stating that "the Supreme Court would be the proper venue as it is a dispute between government institutions." This holding misreads the Constitution's jurisdictional provisions.Section 18(1)(a) of the Constitution grants the Federal Court original jurisdiction over "Questions of constitutionality."

This case presents a pure constitutional question: Does Executive Order 37/25 exceed the President's expressly granted powers under Section 42 of the Constitution?

Section 42 is unambiguous:

The Federal Court has express jurisdiction to decide whether the President exceeded this constitutional limitation. The fact that the case also involves two branches of government does not strip the Federal Court of its constitutional jurisdiction over questions of constitutionality."Executive Orders must only be used as a mechanism by which the President can exert powers expressly granted to the Executive within the Constitution."

Section 20(1)(b) grants the Supreme Court jurisdiction over "Resolving disputes between government institutions," but this jurisdiction is concurrent, not exclusive. Nothing in the Constitution strips the Federal Court of jurisdiction over constitutional questions merely because two branches are involved. If the drafters intended for all inter-branch disputes to go directly to the Supreme Court, Section 18(1)(a)'s grant of jurisdiction over constitutional questions would be meaningless in any case involving government parties.

The Federal Court has jurisdiction, declined to exercise it, and thereby committed reversible error.

III. THIS IS NOT A POLITICAL QUESTION

The Court invoked the political question doctrine, stating this matter should be "resolved through the mechanisms that Congress has available to them (further legislation, oversight, or impeachment)." This represents a fundamental misunderstanding of the political question doctrine and the role of judicial review.Whether the President exceeded constitutional authority under Section 42 is precisely the type of question courts exist to decide. Judicial review of executive actions for constitutional compliance is not a political question - it is the essence of the judicial power vested in the courts by Section 13 of the Constitution.

The Court's reasoning would immunise all executive actions from judicial review whenever Congress has theoretical alternative remedies. This cannot be correct. The Constitution establishes three coequal branches precisely so that each can check the others. The judiciary's check on executive overreach is judicial review, not abdication.

This is the second time this judicial officer has incorrectly invoked the political question doctrine to avoid deciding a justiciable legal question. In ToadKing v. Commonwealth of Redmont [2025] FCR 106, the Court dismissed a challenge to Executive Orders that violated the State Commendations Act's timing requirements, holding:

That case presented a straightforward question of statutory interpretation: Did the President comply with Section 6(1) of the State Commendations Act? Whether executive action complies with statutory requirements is quintessentially justiciable. Yet the Federal Court declined to exercise jurisdiction, incorrectly labelling a legal question as "political."When and how the Executive branch decides its Executive Honors is not something that this court will hear, as it is a political question.

The pattern is clear: this judicial officer has systematically expanded the political question doctrine beyond recognition, using it to avoid deciding cases that clearly fall within the court's jurisdiction. This approach undermines the separation of powers by immunising executive actions from judicial review.

IV. THE DISMISSAL ALLOWS CONSTITUTIONAL VIOLATIONS TO CONTINUE UNCHECKED

The practical effect of the Court's dismissal is that Executive Order 37/25 remains in force despite serious constitutional concerns about whether it exceeds the President's authority under Section 42. The Executive Order purports to create a monopoly on legal advisory organisations, restricting the Legislative Service Commission that Congress created to support its constitutional functions.If individual members of Congress lack standing, ordinary citizens lack standing under the Court's reasoning (contradicting [2025] FCR 87), and "Congress as an institution" must pursue alternative remedies, then no judicial review is available. This immunises executive actions from judicial scrutiny and upends the constitutional system of checks and balances.

V. CONCLUSION

The Federal Court committed reversible error by:1. Contradicting its own precedent in [2025] FCR 87 regarding standing to challenge constitutionality

2. Declining jurisdiction over a constitutional question within its express jurisdiction under Section 18(1)(a) of the Constitution

3. Misapplying the political question doctrine to avoid deciding a justiciable constitutional question

4. Creating an impossible requirement that "Congress as an institution" must sue, contradicting [2025] FCR 87's recognition that individual citizens can challenge constitutionality

This case presents a straightforward legal question: Does Executive Order 37/25 comply with the Constitution's Section 42 requirement that Executive Orders "must only be used as a mechanism by which the President can exert powers expressly granted to the Executive within the Constitution"?

The Federal Court has jurisdiction to answer this question and should have done so. The dismissal should be reversed and the case remanded for decision on the merits.

Supporting Evidence: https://www.democracycraft.net/thre...alth-of-redmont-2025-fcr-87.31073/post-117121

Lawsuit: Adjourned Post in thread 'Ko531 v. Commonwealth of Redmont [2024] FCR 33'

Motion for Sua Sponte dissmisalYour Honor, under rule 2.1 of the court rules and procedures standing is defined as the following:

The defendent fails to fulfil the requists required by subsection 1 of the rule 2.1 and has provided no evidance nor claim that they themselves has received any personal injury from the enaction of the above...

- Suffered some injury caused by a clear second party; or is affected by an application of law.

- The cause of injury was against the law.

- Remedy is applicable under relevant law that can be granted by a favorable decision.

Government Thread 'Constitution'

PREAMBLE

We the people, of the Commonwealth of Redmont, in order to form a more perfect country, establish this Constitution to guarantee the preservation and protection of Justice, promote the general welfare of our citizens, and secure the liberty of our participation in the governance of this country. All citizens and the Government of the Commonwealth of Redmont will abide by these here set principles to unite as an indissoluble nation, the Commonwealth of Redmont.

This Constitution is the highest law of the Commonwealth. It binds all...

- DemocracyCraft

- Replies: 0

- Forum: Rules & Laws

Executive Order Thread 'Executive Order 37/25 - The BAR, Bring it forth.'

By the authority vested in me as President under the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Redmont, I, Pepecuu, the 23rd President of the Commonwealth of Redmont, do declare the following under this Executive Order:

Section 1. The Bar Association of Redmont (BAR)

(1) The BAR is hereby created as a public advisory organization for Redmont's legal sector.

(2) The BAR shall be the only government-endorsed public advisory legal organization that is allowed to operate within the territory of the Commonwealth of Redmont.

(3) The BAR shall encompass individuals that are licensed to...

Section 1. The Bar Association of Redmont (BAR)

(1) The BAR is hereby created as a public advisory organization for Redmont's legal sector.

(2) The BAR shall be the only government-endorsed public advisory legal organization that is allowed to operate within the territory of the Commonwealth of Redmont.

(3) The BAR shall encompass individuals that are licensed to...

- Pepecuu

- Replies: 0

- Forum: Executive Orders

Lawsuit: Dismissed Thread 'ToadKing v. Commonwealth of Redmont [2025] FCR 106'

Case Filing

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF REDMONT

CIVIL ACTION

ToadKing

Plaintiff

v.

Commonwealth of Redmont

Defendant

COMPLAINT

The Plaintiff complains against the Defendant as follows:

WRITTEN STATEMENT FROM THE PLAINTIFF

Between 11 October 2025 and 13 October 2025, the President of the Commonwealth of Redmont issued three Executive Orders awarding state commendations to numerous individuals. These Executive Orders - EO 34/25, EO 35/25, and EO 36/25 - were issued after the conclusion of the 15th Presidential Election...

- ToadKing

- Replies: 3

- Forum: Case Archive