Alexander P. Love

Citizen

Supporter

Popular in the Polls

Legal Eagle

Statesman

Order of Redmont

AlexanderLove

Attorney

- Joined

- Jun 2, 2021

- Messages

- 1,388

- Thread Author

- #1

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF REDMONT

CIVIL ACTION

Galavance (Represented by The Lovely Law Firm)

Plaintiff

v.

The Commonwealth of Redmont

Defendant

COMPLAINT

The Plaintiff complains against the Defendant as follows:

In late June, the President implemented an Executive Order changing certain parameters for the sole purpose of forcing towns to change their government. The elected leader of the Town of Oakridge, Galavance, was forcibly removed by the President of Redmont shortly after this Executive Order came into effect. This case will examine how the rule of a unitary executive can be reconciled with a democratic and elected town Government. The Constitution makes mention of certain parameters for towns that the Government through the Executive may regulate, but many of the regulations published by the Executive are an overreach of its authority and plain unconstitutional. Today, we fight to restore democracy and fight off the step toward authoritarianism that was thus far allowed to occur.

I. PARTIES

1. Galavance (Plaintiff)

2. LilDigiVert (President of Redmont)

3. The Executive Cabinet (Witness)

4. The Town of Aventura (Witness)

II. FACTS

1. President LilDigiVert issued an unconstitutional Executive Order, 19/23 - Town Revisions (link).

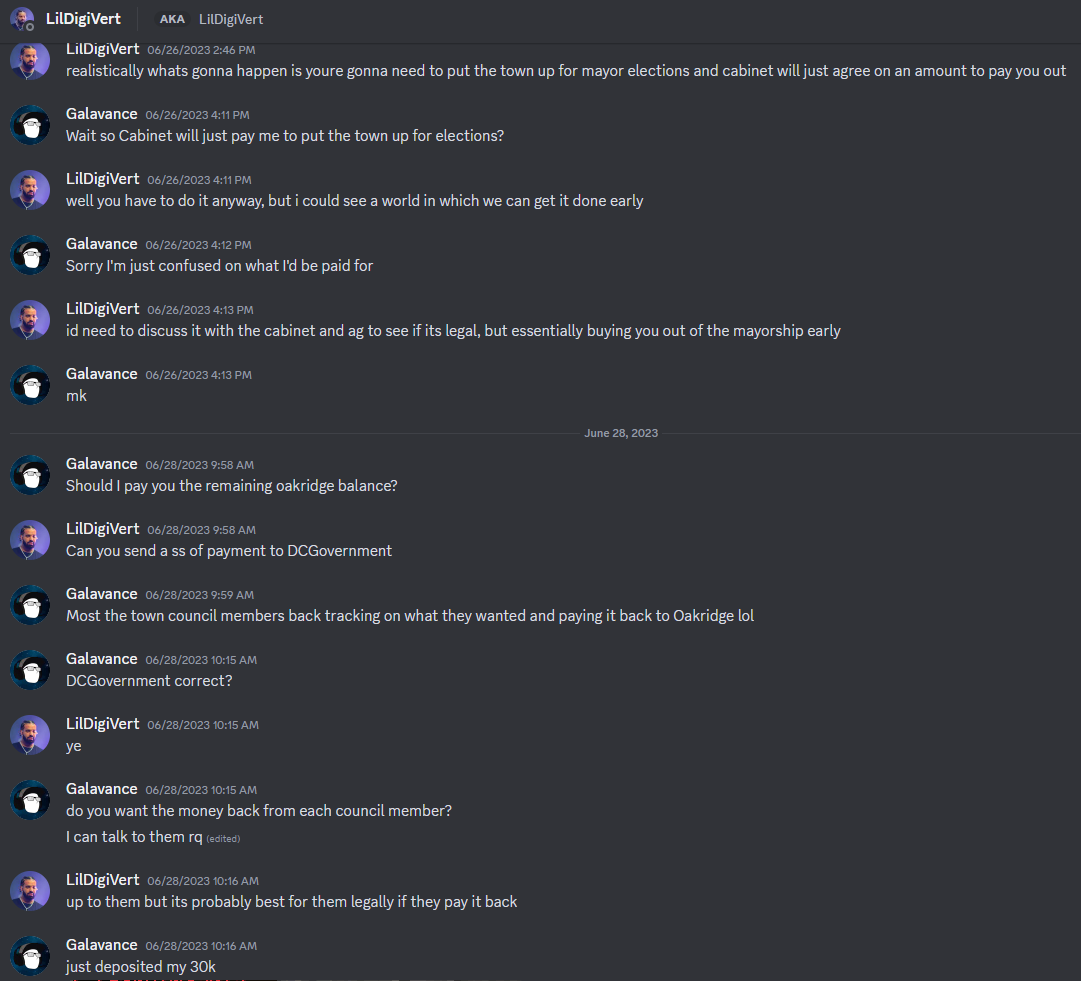

2. The President and Cabinet attempted to "buy" Galavance out of his seat as Mayor.

2. Galavance was removed forcefully and illegally from his position as Mayor of Oakridge by the Executive Branch.

III. CLAIMS FOR RELIEF

1. This Executive Order makes several complex changes that include changes in system of Government. Owner assent was not clearly noted on the Executive Order at the time of passage.

2. Executive orders as defined by the Constitution may only provide for the implementation of existing statute or Constitutional provisions, and may not create or amend the law. This Executive Order creates provisions that in effect serve as legislation when no legislative authority has been delegated to the Executive in this field. There are no existing statutes regarding the Governance of towns (link).

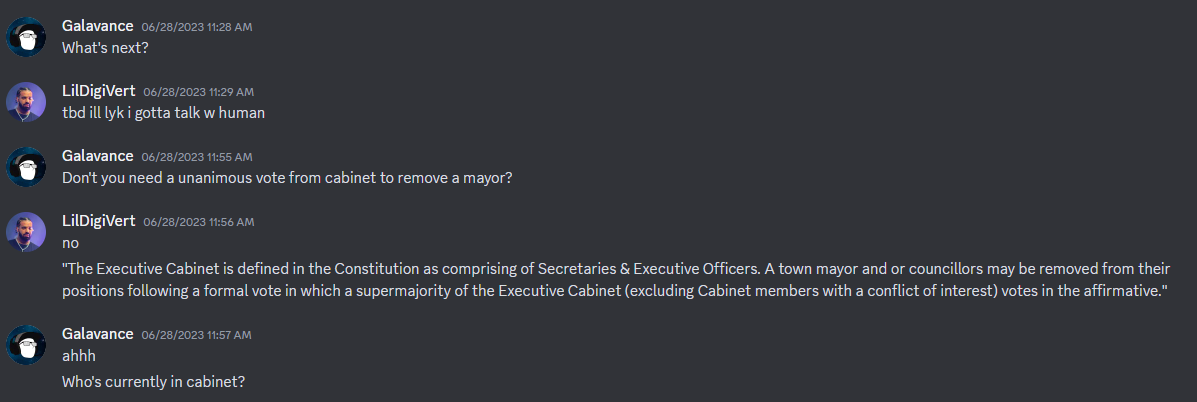

3. "The Executive Cabinet is defined in the Constitution as comprising of Secretaries & Executive Officers. A town mayor and or councillors may be removed from their positions following a formal vote in which a supermajority of the Executive Cabinet (excluding Cabinet members with a conflict of interest) votes in the affirmative" is unconstitutional as the Constitution grants the power for removal of elected officials and other non-Executive officials solely to the legislature via the impeachment process. The President and Cabinet may only remove officials within their Departments, including cabinet officers. Town officials are not members of the Executive Branch, as they are members of the Town Government, elected by and for the residents of that town.

4. The Executive Branch attempted to bribe the Mayor in to resigning his seat as Mayor, which is also an unconstitutional use of appropriations as it was not explicitly authorized by Congress. See the exhibits in Section V.

5. The Executive Branch has exceeded its authority and stepped on the toes of the legislature as well as the governments of the towns themselves, in summary.

6. There is a certain element of common law when it comes to towns. A large part of their existence has occurred outside of the direct purview of the law, and the towns have gained a certain separation from the federal Government in these matters. Towns have their own Constitutions which take precedence when it comes to the affairs of a town. The Redmont Constitution does not contain a Supremacy Clause like most Constitutions that govern federalist countries do, therefore, not every action of the Redmont federal government is allowed to supersede that of the towns.

7. Because there is a large level of autonomy granted to the towns, routine tasks such as the democratic election of a Mayor and town council should be done without the regulation and interference of the federal Government, particularly the President's arbitrary and capricious Executive Orders. Forcing Mayors to be removed from their positions in town government is not of reasonable interest to the federal Government and is entirely outside of its scope.

Footnote: Several Constitutional questions are at play here, including that of the role of the Executive in contrast to that of the Legislature. This also concerns the federalist relationship between towns and the Government of Redmont. This case therefore should withstand any motion to dismiss prima facie.

IV. PRAYER FOR RELIEF

The Plaintiff seeks the following from the Defendant:

1. For all illegal provisions contained within Executive Order 19/23 to be struck.

2. For all removed persons from town councils including Mayors under this Executive Order's provisions to be reinstated.

3. $50,000 in consequential damages falling under the category "The Loss of Enjoyment in Redmont" (see The Legal Damages Act [link]) as my client is now unable to enjoy his lawful job he held in Oakridge, and by extension, Redmont, due to these illegal actions.

4. $50,000 in consequential damages falling under the category "Humiliation" as my client now has a removal from office on his record, which to voters, is seen as a negative. This hinders my client's ability to fully participate in politics due to this humiliating removal.

5. $50,000 in consequential damages falling under the category "Emotional Damages" as my client was content and happy in his lifestyle which was abruptly and unduly interrupted.

6. $5,000 in legal fees, the cost of The Lovely Law Firm's involvement in this case affirmed by myself.

V. EVIDENCE

By making this submission, I agree I understand the penalties of lying in court and the fact that I am subject to perjury should I knowingly make a false statement in court.

DATED: This 16th day of July, 2023

CIVIL ACTION

Galavance (Represented by The Lovely Law Firm)

Plaintiff

v.

The Commonwealth of Redmont

Defendant

COMPLAINT

The Plaintiff complains against the Defendant as follows:

In late June, the President implemented an Executive Order changing certain parameters for the sole purpose of forcing towns to change their government. The elected leader of the Town of Oakridge, Galavance, was forcibly removed by the President of Redmont shortly after this Executive Order came into effect. This case will examine how the rule of a unitary executive can be reconciled with a democratic and elected town Government. The Constitution makes mention of certain parameters for towns that the Government through the Executive may regulate, but many of the regulations published by the Executive are an overreach of its authority and plain unconstitutional. Today, we fight to restore democracy and fight off the step toward authoritarianism that was thus far allowed to occur.

I. PARTIES

1. Galavance (Plaintiff)

2. LilDigiVert (President of Redmont)

3. The Executive Cabinet (Witness)

4. The Town of Aventura (Witness)

II. FACTS

1. President LilDigiVert issued an unconstitutional Executive Order, 19/23 - Town Revisions (link).

2. The President and Cabinet attempted to "buy" Galavance out of his seat as Mayor.

2. Galavance was removed forcefully and illegally from his position as Mayor of Oakridge by the Executive Branch.

III. CLAIMS FOR RELIEF

1. This Executive Order makes several complex changes that include changes in system of Government. Owner assent was not clearly noted on the Executive Order at the time of passage.

2. Executive orders as defined by the Constitution may only provide for the implementation of existing statute or Constitutional provisions, and may not create or amend the law. This Executive Order creates provisions that in effect serve as legislation when no legislative authority has been delegated to the Executive in this field. There are no existing statutes regarding the Governance of towns (link).

3. "The Executive Cabinet is defined in the Constitution as comprising of Secretaries & Executive Officers. A town mayor and or councillors may be removed from their positions following a formal vote in which a supermajority of the Executive Cabinet (excluding Cabinet members with a conflict of interest) votes in the affirmative" is unconstitutional as the Constitution grants the power for removal of elected officials and other non-Executive officials solely to the legislature via the impeachment process. The President and Cabinet may only remove officials within their Departments, including cabinet officers. Town officials are not members of the Executive Branch, as they are members of the Town Government, elected by and for the residents of that town.

4. The Executive Branch attempted to bribe the Mayor in to resigning his seat as Mayor, which is also an unconstitutional use of appropriations as it was not explicitly authorized by Congress. See the exhibits in Section V.

5. The Executive Branch has exceeded its authority and stepped on the toes of the legislature as well as the governments of the towns themselves, in summary.

6. There is a certain element of common law when it comes to towns. A large part of their existence has occurred outside of the direct purview of the law, and the towns have gained a certain separation from the federal Government in these matters. Towns have their own Constitutions which take precedence when it comes to the affairs of a town. The Redmont Constitution does not contain a Supremacy Clause like most Constitutions that govern federalist countries do, therefore, not every action of the Redmont federal government is allowed to supersede that of the towns.

7. Because there is a large level of autonomy granted to the towns, routine tasks such as the democratic election of a Mayor and town council should be done without the regulation and interference of the federal Government, particularly the President's arbitrary and capricious Executive Orders. Forcing Mayors to be removed from their positions in town government is not of reasonable interest to the federal Government and is entirely outside of its scope.

Footnote: Several Constitutional questions are at play here, including that of the role of the Executive in contrast to that of the Legislature. This also concerns the federalist relationship between towns and the Government of Redmont. This case therefore should withstand any motion to dismiss prima facie.

IV. PRAYER FOR RELIEF

The Plaintiff seeks the following from the Defendant:

1. For all illegal provisions contained within Executive Order 19/23 to be struck.

2. For all removed persons from town councils including Mayors under this Executive Order's provisions to be reinstated.

3. $50,000 in consequential damages falling under the category "The Loss of Enjoyment in Redmont" (see The Legal Damages Act [link]) as my client is now unable to enjoy his lawful job he held in Oakridge, and by extension, Redmont, due to these illegal actions.

4. $50,000 in consequential damages falling under the category "Humiliation" as my client now has a removal from office on his record, which to voters, is seen as a negative. This hinders my client's ability to fully participate in politics due to this humiliating removal.

5. $50,000 in consequential damages falling under the category "Emotional Damages" as my client was content and happy in his lifestyle which was abruptly and unduly interrupted.

6. $5,000 in legal fees, the cost of The Lovely Law Firm's involvement in this case affirmed by myself.

V. EVIDENCE

By making this submission, I agree I understand the penalties of lying in court and the fact that I am subject to perjury should I knowingly make a false statement in court.

DATED: This 16th day of July, 2023

Last edited: