- Thread Author

- #1

Username: Muggy21

I am representing a client

Who is your Client?: lukeyyyMC_

File(s) attached

What Case are you Appealing?: [2025] FCR 30

Link to the Original Case: RaiTheGuy v. lukeyyyMC_ [2025] FCR 30

Basis for Appeal: I. CONGRESS ACTS WITH INTENT, THE COURTS CAN'T GO BEYOND IT.

1. Laws are interpreted both for their context and their underlying meaning ("spirit of the law").

2. This underlying meaning can be ascertained by reasonable analysis, societal impact, or on a reasoning of common law.

3. The Courts, by virtue of separation of powers between the branches, are not able to abstract authorities not explicitly nor reasonably ascertained from statute.

4.Judicial expansion of a statute’s meaning beyond its reasonable intent would, in effect, substitute the court’s will for the legislature’s.

5. To maintain fidelity to constitutional design, courts must confine their analysis to the statutory text and its necessary implications, avoiding creation of new rights or obligations not contemplated by Congress.

6.Any ambiguity in legislative drafting must be resolved in a manner consistent with legislative history and purpose, but never in a way that confers powers or duties outside the plain scope of the law.

2. THE COURT MIS-APPREHENDED THE MEANING OF "INSTITUTION" UNDER LAW

1. The Commercial Standards Act treats “gaming institutions” as a special category subject to oversight, which shows that the legislature intended only certain organized establishments.

2. The Cool DEC Casino Investigation Act was enacted specifically to close a loophole where the Department of Commerce (formerly DEC) lacked warrant authority to investigate casinos advertising odds. The Act permitted warrantless inspections only for casinos that had “displayed odds,” recognizing that these operations held themselves out as organized, quasi-public enterprises.

3. By singling out casinos with displayed odds, the legislature demonstrated that not every gambling business was to be treated as an institution, only those that created a reliance relationship with the public by advertising a system of play. Small, private, or informal gambling operations were not the focus of the law.

4. Informal or private gambling arrangements were not the target of the Act.

5. Accordingly, the statutory scheme demonstrates that “institution” was meant to denote formal, outward-facing casinos subject to regulatory reliance, not every gambling activity, and the Court’s broader interpretation impermissibly expands the scope of the law beyond both its text and its legislative history.

3. COMMERCIAL STANDARDS ACT ONLY APPLIES TO PHYSICAL CASINOS/GAMING SALONS

1. Section 15(1) of the Commercial Standards Act expressly imposes obligations only on “gaming institutions” with respect to “gaming machines and activities.” The natural reading of this language confines its scope to physical gambling devices or games where odds can be displayed.

2. The reference to “a visible area adjacent to the machine/activity” further reinforces this narrow construction, since auctions do not involve physical gaming machines or chance-based activities where statistical odds are relevant.

3. Legislative history, including the Cool DEC Casino Investigation Act, shows that oversight was designed to address false odds in casinos, not transactions like auctions. This demonstrates that the purpose was consumer protection in gambling environments, not market regulation of property sales.

4. To stretch §15 to cover bidding at auction would create absurdity, requiring auctioneers to post “odds” where none exist, thereby contradicting both the plain text and legislative intent.

5. Therefore, §15 must be interpreted as applying only to physical casino-style gambling institutions, not to auction bids or other commercial dealings outside the gambling context.

4. COURT ERR'D IN INTERPRETATING GAMING LAWS.

1. Gambling, in its ordinary sense, requires three elements: (a) a wager or stake of value, (b) an element of chance, and (c) the possibility of winning or losing a prize. These elements together distinguish gambling from other forms of recreation or speculation.

2. Gaming, by contrast, is a broader category of structured play. It may involve chance and skill but does not necessarily include a wager or prize, and therefore cannot be assumed to constitute gambling.

3. The Court errs in collapsing the two categories. Just as elections cannot be forced into the statutory categories of “terrorism,” “war,” or “assassination” by mere analogy, ordinary gaming cannot be transformed into gambling by stretching the definition. A contract or activity must actually involve the core elements of gambling, not merely “amount to” it by a loose equivalence.

4. Consider the example of a “loot box” in a video game: a player purchases the box and is guaranteed to receive it. The element of chance lies only in the specific contents, not in whether the player loses their payment. The essential feature of gambling, a stake placed at risk for possible total loss, is absent.

5. For gambling to exist, the stake must be subject to a binary outcome: either forfeiture or conversion into a prize. Here, the player never loses their consideration; they always receive the purchased item. The subjective variation in value does not substitute for the win/lose structure that defines gambling.

6. Since gambling requires all three elements, and the activity at issue lacks both a true wager and a true prize, it cannot be classified as gambling. Gaming may overlap with gambling in some contexts, but the two are not synonymous.

7. Collapsing the categories would erase their definitional boundaries and flunk basic canons of interpretation. A category cannot be expanded simply because it could be rhetorically stretched to fit; it must actually involve the prohibited or regulated conduct.

5. FRAUD FINDINGS WERE MISAPPLIED

1. The Court erred in holding that the “Filthy Rich Mystery Box” title was fraudulent. Such language is textbook puffery, non-literal advertising exaggeration long recognized as non-actionable (see CSA § 18 (8))

2. Collectible value is inherently subjective. Departures from CPI metrics do not equate to fraud, especially when regulators themselves admit there is no formal process for pricing or approval.

3. Fraud requires intent to mislead with material falsity. Here, bidders voluntarily assumed the known risk of uncertain contents. Exaggerated branding and subjective valuation do not meet the threshold of intentional deception.

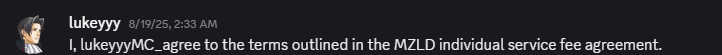

Supporting Evidence:

I am representing a client

Who is your Client?: lukeyyyMC_

File(s) attached

What Case are you Appealing?: [2025] FCR 30

Link to the Original Case: RaiTheGuy v. lukeyyyMC_ [2025] FCR 30

Basis for Appeal: I. CONGRESS ACTS WITH INTENT, THE COURTS CAN'T GO BEYOND IT.

1. Laws are interpreted both for their context and their underlying meaning ("spirit of the law").

2. This underlying meaning can be ascertained by reasonable analysis, societal impact, or on a reasoning of common law.

3. The Courts, by virtue of separation of powers between the branches, are not able to abstract authorities not explicitly nor reasonably ascertained from statute.

4.Judicial expansion of a statute’s meaning beyond its reasonable intent would, in effect, substitute the court’s will for the legislature’s.

5. To maintain fidelity to constitutional design, courts must confine their analysis to the statutory text and its necessary implications, avoiding creation of new rights or obligations not contemplated by Congress.

6.Any ambiguity in legislative drafting must be resolved in a manner consistent with legislative history and purpose, but never in a way that confers powers or duties outside the plain scope of the law.

2. THE COURT MIS-APPREHENDED THE MEANING OF "INSTITUTION" UNDER LAW

1. The Commercial Standards Act treats “gaming institutions” as a special category subject to oversight, which shows that the legislature intended only certain organized establishments.

2. The Cool DEC Casino Investigation Act was enacted specifically to close a loophole where the Department of Commerce (formerly DEC) lacked warrant authority to investigate casinos advertising odds. The Act permitted warrantless inspections only for casinos that had “displayed odds,” recognizing that these operations held themselves out as organized, quasi-public enterprises.

3. By singling out casinos with displayed odds, the legislature demonstrated that not every gambling business was to be treated as an institution, only those that created a reliance relationship with the public by advertising a system of play. Small, private, or informal gambling operations were not the focus of the law.

4. Informal or private gambling arrangements were not the target of the Act.

5. Accordingly, the statutory scheme demonstrates that “institution” was meant to denote formal, outward-facing casinos subject to regulatory reliance, not every gambling activity, and the Court’s broader interpretation impermissibly expands the scope of the law beyond both its text and its legislative history.

3. COMMERCIAL STANDARDS ACT ONLY APPLIES TO PHYSICAL CASINOS/GAMING SALONS

1. Section 15(1) of the Commercial Standards Act expressly imposes obligations only on “gaming institutions” with respect to “gaming machines and activities.” The natural reading of this language confines its scope to physical gambling devices or games where odds can be displayed.

2. The reference to “a visible area adjacent to the machine/activity” further reinforces this narrow construction, since auctions do not involve physical gaming machines or chance-based activities where statistical odds are relevant.

3. Legislative history, including the Cool DEC Casino Investigation Act, shows that oversight was designed to address false odds in casinos, not transactions like auctions. This demonstrates that the purpose was consumer protection in gambling environments, not market regulation of property sales.

4. To stretch §15 to cover bidding at auction would create absurdity, requiring auctioneers to post “odds” where none exist, thereby contradicting both the plain text and legislative intent.

5. Therefore, §15 must be interpreted as applying only to physical casino-style gambling institutions, not to auction bids or other commercial dealings outside the gambling context.

4. COURT ERR'D IN INTERPRETATING GAMING LAWS.

1. Gambling, in its ordinary sense, requires three elements: (a) a wager or stake of value, (b) an element of chance, and (c) the possibility of winning or losing a prize. These elements together distinguish gambling from other forms of recreation or speculation.

2. Gaming, by contrast, is a broader category of structured play. It may involve chance and skill but does not necessarily include a wager or prize, and therefore cannot be assumed to constitute gambling.

3. The Court errs in collapsing the two categories. Just as elections cannot be forced into the statutory categories of “terrorism,” “war,” or “assassination” by mere analogy, ordinary gaming cannot be transformed into gambling by stretching the definition. A contract or activity must actually involve the core elements of gambling, not merely “amount to” it by a loose equivalence.

4. Consider the example of a “loot box” in a video game: a player purchases the box and is guaranteed to receive it. The element of chance lies only in the specific contents, not in whether the player loses their payment. The essential feature of gambling, a stake placed at risk for possible total loss, is absent.

5. For gambling to exist, the stake must be subject to a binary outcome: either forfeiture or conversion into a prize. Here, the player never loses their consideration; they always receive the purchased item. The subjective variation in value does not substitute for the win/lose structure that defines gambling.

6. Since gambling requires all three elements, and the activity at issue lacks both a true wager and a true prize, it cannot be classified as gambling. Gaming may overlap with gambling in some contexts, but the two are not synonymous.

7. Collapsing the categories would erase their definitional boundaries and flunk basic canons of interpretation. A category cannot be expanded simply because it could be rhetorically stretched to fit; it must actually involve the prohibited or regulated conduct.

5. FRAUD FINDINGS WERE MISAPPLIED

1. The Court erred in holding that the “Filthy Rich Mystery Box” title was fraudulent. Such language is textbook puffery, non-literal advertising exaggeration long recognized as non-actionable (see CSA § 18 (8))

2. Collectible value is inherently subjective. Departures from CPI metrics do not equate to fraud, especially when regulators themselves admit there is no formal process for pricing or approval.

3. Fraud requires intent to mislead with material falsity. Here, bidders voluntarily assumed the known risk of uncertain contents. Exaggerated branding and subjective valuation do not meet the threshold of intentional deception.

Supporting Evidence:

Attachments

Last edited: